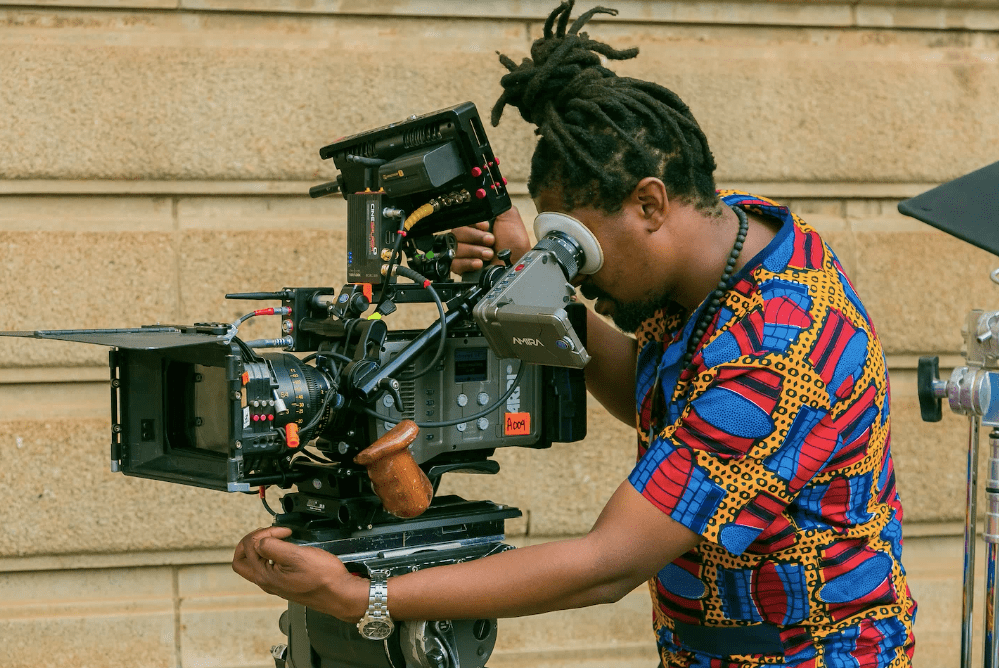

Arie and Chuko Esiri on the set of “Eyimofe.”

There are still challenges domestically, though, particularly for indie or art house movies, Esiri said. Even in a country like Nigeria, home to a huge commercial film industry, promoting “Eyimofe” was difficult.

“The domestic market is saturated with explicitly commercial fare, art house or indie film was an entirely new proposition,” Esiri said. “The mechanisms for marketing were not particularly effective and it will be something we shall have to continue to work on.”

And still, too often, movies from the continent are linked to a single auteur rather than a broader industry, Dia said. But now, a whole generation of African filmmakers is emerging, he said, telling stories in ways that feel true using their own traditions, cultures and folktales.

That new generation, Haroun said, is tackling social and political issues in fresh ways. He pointed to Mati Diop’s “Atlantique” as one example, and Dia’s work in “Nafi’s Father” as another. Which is to say: scarcity is not the issue. The art is there.

A cinephile culture on the continent is developing, too. The Panafrican Film Festival, commonly known as FESPACO, the Africa Movie Academy Awards, and film festivals in Durban, South Africa, Zanzibar and Egypt all award films from the continent. This, Adejunmobi said, is where the recognition is really coming from.

In spite of everything, film in Africa continues to grow. And the work is exquisite — just see the rich choreography in “Night of the Kings,” the soft light of “Lingui,” the tension of “Nafi’s Father,” the challenges in “Eyimofe” deliciously depicted in 16mm film. These all just in the last few years.

African filmmakers are not waiting for Americans to offer a seat in a section. They’re bringing their instruments to the orchestra anyway.

Leave a comment